The Canadian Northern Energy Corridor Project

NOTE: This page is under construction!!

PREAMBLE

The Senior Engineer of AscenTrust, LLC., was born in the hospital at McLennan Alberta, on January 01, 1948, raised on a farm located on highway #2, near LacMagloire, graduated class valadictorian at Langlois School in Guy in Northern Alberta and graduated, in Electrical and Computing Engineering, with Distinction, in 1969, at the University of Alberta in Edmonton.

AscenTrust, LLC., an existing Texas corporation, wholly owned by it's Senior Engineer, will provide the overall Project Engineering, Project Design, Project Management and Construction Management for all projects financed through the effort of IDFS, INC., the Heritage Fund of Alberta and JPMorgan-CHASE BANK

Preliminary discussion on the scope document for The Canadian Northern Corridor (CNC) have been ongoing for several weeks.

The Canadian Northern Corridor (CNC) shall consist of the following economic transmission components:

- 1. The most important economic piece of the transportation corridor are the natural gas and hydrocarbon pipelines

- 2. The second economic piece is the high-voltage Direct Current, underground transmission system

- 3. The fiber-optic SCADA and communication system

The transportation portion of the corridor shall consist of the following items:

- 1. An all-weather paved highway to transport men and materials for the construction of the components of the Energy Corridor.

- 2. A rail line connecting the port on the west coast with the port on the east coast of Canada.

The manpower training portion of The Canadian Northern Corridor (CNC) will provide training for the The Indigenous Nations (First Nations and Inuits in Canada) . Much of the manpower used to construct The Canadian Northern Corridor (CNC) project will be trained from individuals from the First nations in the areas contiguous with the Corridor.

Introduction

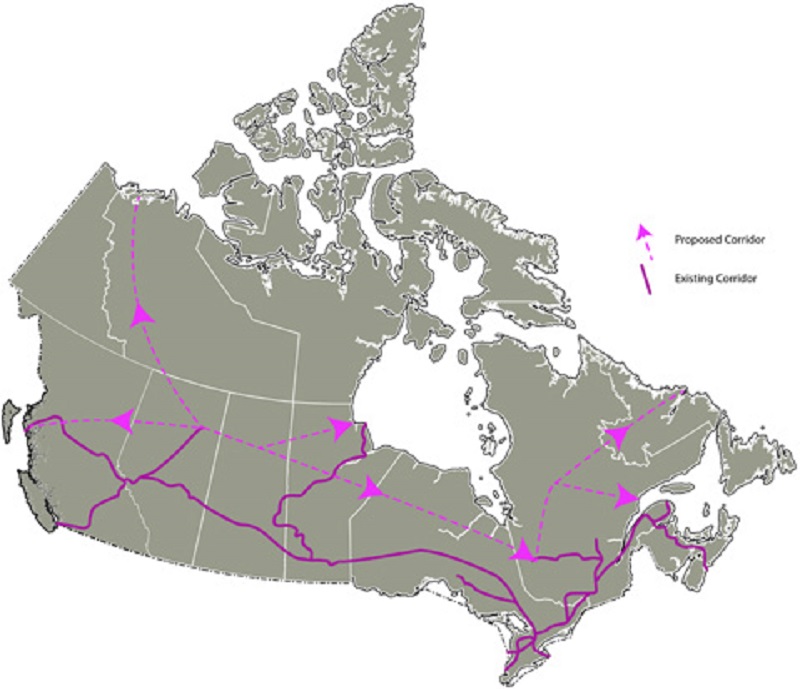

The Canadian Northern Corridor (CNC) was originally conceptualized as a multi-modal (road, rail, pipeline, electrical transmission and communication) transportation corridor through the Northern portions of the provinces from the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic. It is our intention to include three gigawatts of natural gas fired, combined-cycle power production to be tied to the high-voltage Direct Current, underground transmission system. The power production facilities will be connected directly to feed the local grid. The excess electrical production will be added to the high voltage transmission line which will extend from the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic.

The Canadian Northern Corridor (CNC), as we propose,will be a multi-use corridor infrastructure megaproject spanning Canada's east-west mid-latitude with several northern spurs, approximately 7,000 to 10,000 km long and costing roughly $200–300 billion. The concept was originally outlined by academics at the University of Calgary School of Public Policy: Canadian Northern Corridor Special Series. The financing of the Northern Energy Corridor, as we propose, would be essentially financed by the participation of Global Sovereign Wealth Funds and would be initiated by an initial investment from the Heritage Fund of Alberta and participation from JPMorgan-CHASE BANK.

The primary goal of this project is to provide international access to the oil and gas resources of the province of Alberta. The corridor would facilitate the transport a full range of export commodities efficiently to port facilities on all three coasts while also improving economic development and living conditions in remote areas.

This infrastructure would improve access for Canadian goods to alternative markets, assist with trade diversification, enhance regional development and interregional trade opportunities in Canada, support northern and Indigenous economic and social development goals along with Arctic sovereignty objectives, mitigate environmental risks through monitoring and surveillance within a contained footprint and reduce the emissions intensity of transportation in Canada’s north and near-north.

In initial concept, the Northern Corridor would be approximately 7000 km in length. It would largely follow the boreal forest in the northern part of the west, with a spur along the Mackenzie Valley, and then southeast from the Churchill area to northern Ontario and the “Ring of Fire” area; the corridor would then traverse northern Quebec to Labrador, with augmented ports. The right-of-way would have room for roads, rail lines, pipelines and transmission lines, and would interconnect with the existing (southern-focused) transportation network.

To move forward on the Northern Corridor will require participation from the Federal government. The Federal Government of Canada will need to create the environment in which private investment, properly regulated, can be applied to projects without intransigent “one-off” regulatory processes for a new right of way for each project. The establishment of a multi-modal right-of-way facilitates a long-term, integrated approach to the approval, construction and operation of infrastructure. Another benefit of the Northern Corridor concept is that comprehensive approaches, which due to their scale allow for accommodation of many diverse interests, can (paradoxically) be more achievable than a series of incremental steps.

The objective of this webpage is to examine the potential of the Northern Corridor and outline the range of issues that would need to be studied in detail to determine the viability.

The process being put in-place by the Senior Engineer to re-start the licensing and construction of the Keystone XL Pipeline Project (Phase IV) is the reason for the creation of this webpage.

An important driver for the study of a new, integrated Canadian transportation corridor is the now apparent opportunity cost of Canada’s restricted ability to export commodities to world markets. Examples of this include energy products where, notwithstanding the post-2014 decline in global oil market prices, the international prices for oil and natural gas remain generally higher than those realizable in the currently accessible North American market. 7 Agricultural and forestry have also faced costly transportation bottlenecks prompting the Forestry Products Association of Canada to make calls on the federal government for longer-term transportation infrastructure planning horizons and a shift away from north-south transportation towards east-west transportation. Such a shift to the development of east-west transportation infrastructure is needed in order to match a long-term trend away from land-based export (south to the U.S.) and towards access to tidewater through Canadian ports.

Federal, provincial and territorial ministers responsible for energy and mines have already recognized a lack of infrastructure as a limiting factor in the further development of Canada’s mining and oil and gas commodity sectors. Following their 2014 conference, they released a discussion paper, which stated that: “A lack of infrastructure in certain regions (e.g. the North) and industry segments (e.g. oil and gas extraction, oil sands and liquefied natural gas) are creating bottlenecks that have contributed to higher transportation costs, project delays and, in some cases, lower revenues.”

The construction and maintenance of the Northern Corridor will contribute a significant increase in economic development in the north, accompanied by increases to the standard of living, including reductions in the cost of living. Canada’s northern communities currently face substantially higher living costs than those further south. The cost of goods and services in the north is more than 25 per cent higher than in the rest of Canada. This cost differential is primarily driven by high transportation costs that result from poor infrastructure. A Northern Corridor would go a long way towards reducing these cost differentials as well as providing new employment and business opportunities for northern residents.